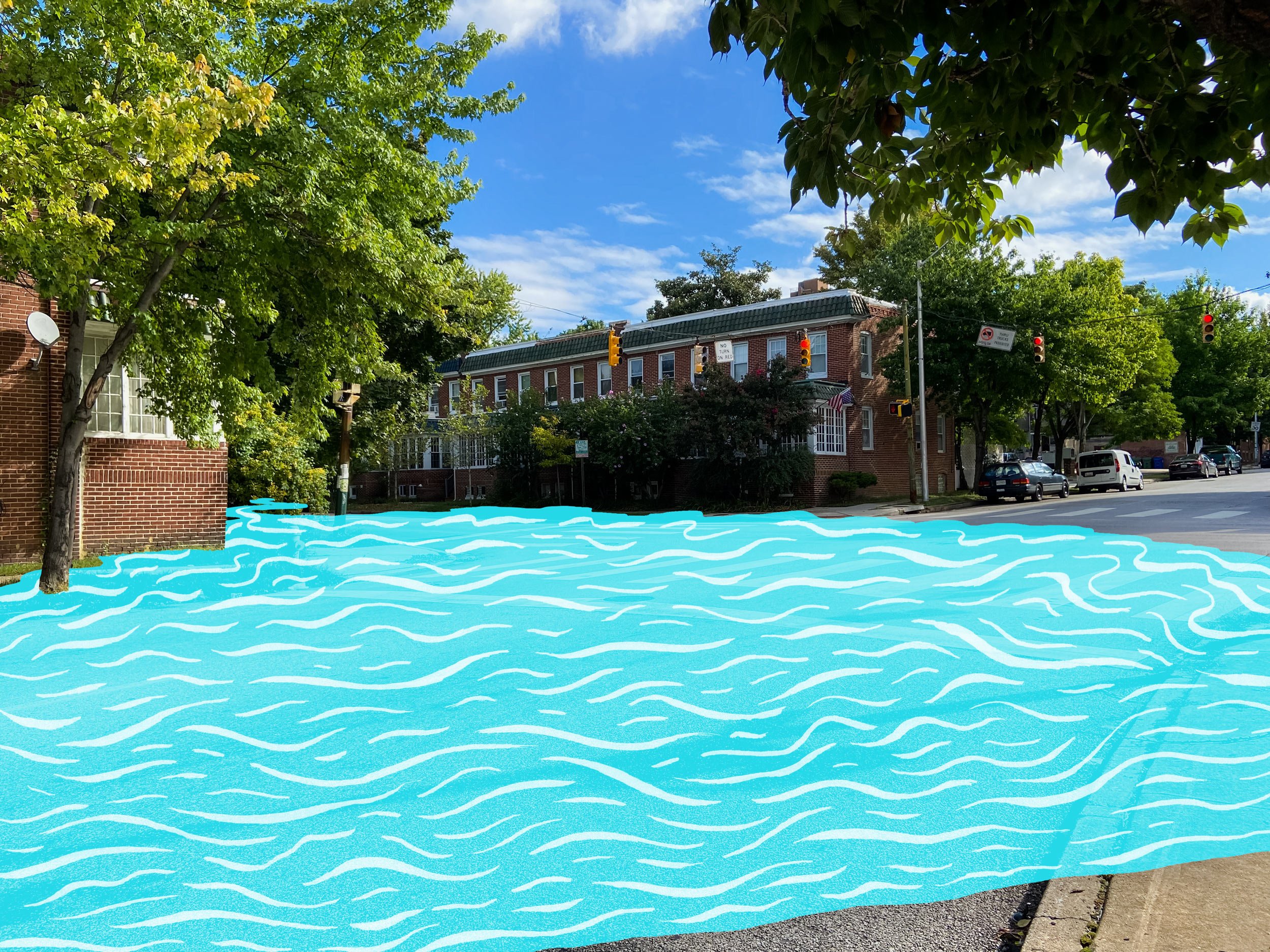

Site 4. 28th Street

Ghost Rivers: Sumwalt Run

Imagine a cold, bright day in the winter of 1895.

If you stood at this spot, you’d be in the middle of a deep valley, looking across a placid pond stretching to the south edge of Wyman Park Dell. From your perch atop a wide earthen dam, you might see boys and girls carefully making their way down a steep, snow-packed path, ice skates clanking in their hands.

Here on Sumwalt’s Ice Pond generations of Baltimore kids came to skate in the winter and swim in the summer. Before climate change reshaped the seasons, reliably cold weather also turned ponds into business opportunities. Frozen water was sawed from ponds and rivers, stored in insulated ice houses until the summer months, then sold to fish markets, creameries, and home ice boxes across the city (electric refrigerators wouldn’t become common until the 1940s).

Winter – A Skating Scene. 1868, Winslow Homer.

David Sumwalt, son of a local land- and quarry-owner, joined the rapidly growing ice industry in 1845 from a large plot of land that encompassed this stream and three ponds. Thanks to this reliable ice source close to the city, the Sumwalt Ice & Coal Company became one of the city’s first ice distributors. Throughout the warmer months, Sumwalt horse carts clattered over the cobblestones of Baltimore, delivering ice to thousands of households. Between ice harvests, Sumwalt charged the public 15 cents admission for ice skating (or free for Sumwalt’s customers).

A shift to manufactured ice made the ponds less profitable, and in 1908 the city buried sections of Sumwalt Run in a storm sewer, bypassing the pond. Developers began filling in the valley, building houses around the former pond. These new neighbors found its stagnant waters a mosquito-y nuisance. Aiming to combat malaria and other diseases, the city drained the remaining pond in 1914, erasing this body of water and closing a chapter of Baltimore history.

water commodified

An ice wagon making deliveries in Baltimore, ca. 1900. During the winter, when demand for ice was low, Sumwalt carts delivered coal for heating their customers’ homes. (Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture)

““In those days the snow came in December and the hills around the pond were covered with it for the most part until the latter part of February.””

White Hall, the home of ice entrepreneur David Sumwalt (and his successor Edward Green), overlooked Sumwalt’s Ice Pond. The house stood just west of where 28th Street and Maryland Avenue intersect today. (Courtesy Special Collections, Enoch Pratt Free Library)

This 1896 map shows the ice pond and a large ice house just below the dam.

A group of boys swims in an unidentified stream and pond near Baltimore, ca. 1900–1910. (Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1967.11.433)