SITE 2. WYMAN PARK DELL at 29th Street

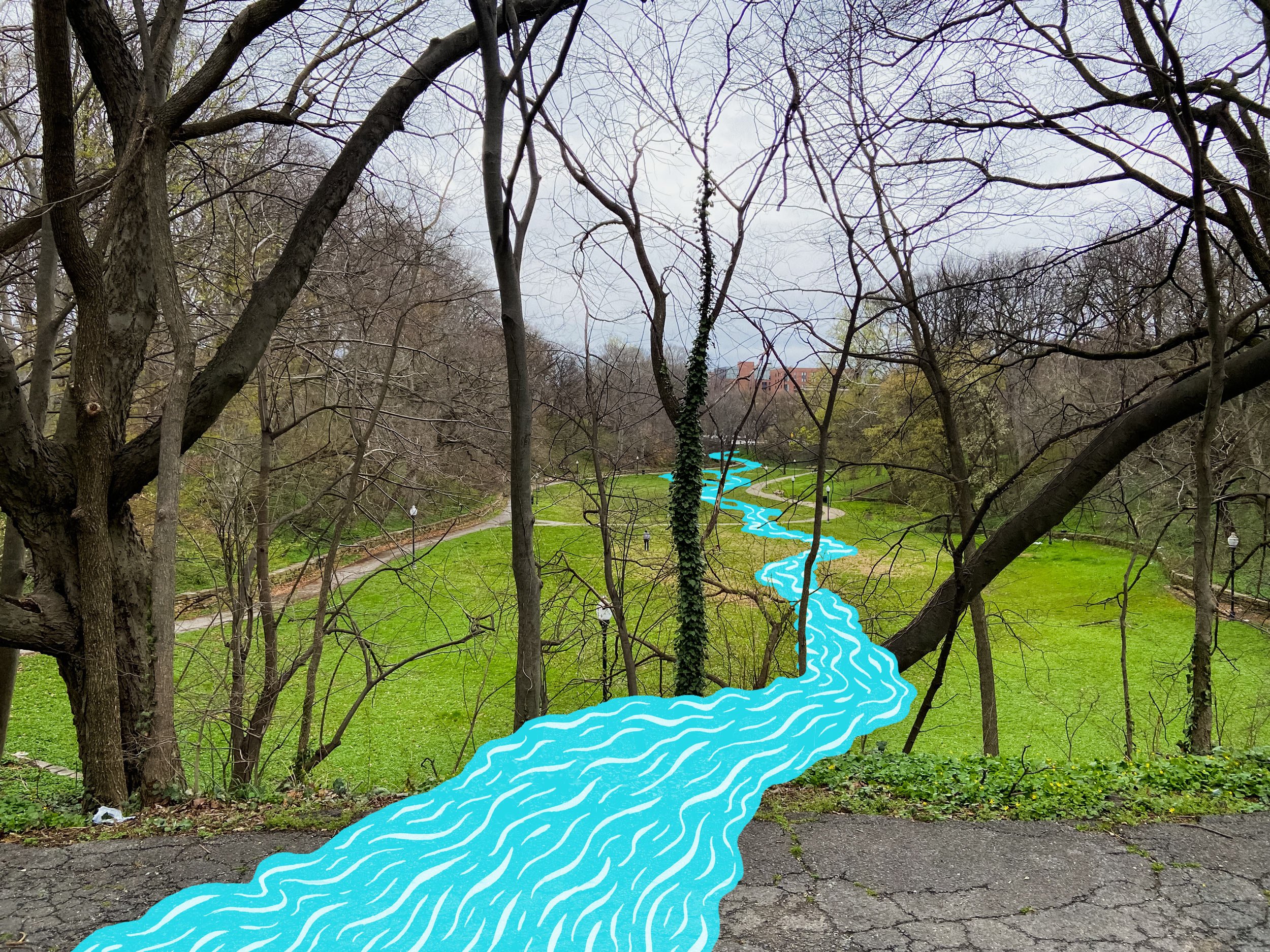

GHOST RIVERS: SUMWALT RUN

In the late 1800s, the sharp corners of a booming city elbowed into the soft edges of streams and rolling fields.

New housing blocks and factories sprawled chaotically across Baltimore’s pastoral fringes. In the face of this relentless development, the Citizens’ Improvement Association of North Baltimore and landowner William Wyman petitioned to preserve a portion of the Sumwalt Run valley here north of 29th Street for use as a public park.

In 1902 Baltimore hired pioneering landscape architects Olmsted Brothers Co. to plan a network of greenways and parks throughout the growing city. The Olmsteds specialized in designing public green spaces woven into the urban grid, a radical idea at the time. Firm founder Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. advocated that “exposure to natural scenery” improved people’s mental and physical health, a theory now confirmed by modern research.

Part of the Olmsted plan recommended preserving Baltimore’s stream valleys, including parts of Sumwalt Run, as links in a green necklace of parks draped across the city. Early sketches for Wyman Park Dell show wooded paths and footbridges crossing Sumwalt Run as it flowed through the park. But before this plan could be realized, unchecked development blasted north, burying sections of the stream below the streets and rowhomes of Charles Village, and destroying natural landscapes that the Olmsteds had hoped to preserve. Forced to scale back their vision of wooded valleys and parkways winding across the city, the Olmsteds instead chose to bury Sumwalt Run’s remaining aboveground fragment beneath a large, curving lawn, creating a more manicured urban oasis here at the Dell.

Early Olmsted Brothers sketches for Wyman Park Dell included a preserved section of Sumwalt Run. (Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site)

Layers upon layers

The 2900 block of Saint Paul Street, looking north towards Sumwalt Run. (Courtesy SS. Philip & James Church archives)

It may seem incongruous today to imagine a block of Baltimore’s urban rowhouses dead-ending at a wild creek or cowpasture. But human landscapes often begin in uncomfortable juxtaposition and competition with landscapes built by water, plants, and animals. Our homes and highways obscure what came before, lane by lane, lot by lot.

““There, at Saint Paul and Thirtieth Streets, as I very well remember, stood a steep bank, on the southern side of the run, overgrown with beech trees and very beautiful.””

The Olmsted Plan

Map of Baltimore showing existing and proposed park lands. (Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site)

The Olmsted Plan of 1904 proposed a connected series of parks and greenways weaving across Baltimore. Although many of its recommendations (such as a proposed Jones Falls Park) were never realized, key parts of this visionary plan became a reality, including beautiful parks along Herring Run and the Gwynn’s Falls. Today the City and a group of dedicated organizations and individuals are working to reimagine elements of this century-old plan through the Baltimore Green Network.

Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., John Charles Olmsted, and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. The landscape architecture firm led by the Olmsteds transformed Baltimore and many other cities with their park designs and progressive approach to urban planning. (Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site)

Resources & Readings

Baltimore Green Network Plan. Baltimore City Department of Planning, 2018

Constructing Nature: The Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted by Anne Whiston Spirn, in Uncommon Ground: Toward Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, ed. William Cronon. Norton, 1996.